Below are speaker notes for a talk I gave at UCD as part of the Irish Health Economics masterclass titled "Behavioural health policy: mental health, measured human experience, and ethics" on March 14th 2022. The talk itself is interactive and not fully scripted. Hopefully the notes below will help if anyone wants to source various material or follow up on any points.

I am going to speak about some directions in integrating mental health and human experience measures into policy appraisal and evaluation. At a very broad level, I am interested in the context whereby mental health and measures of human experience are entering back into economic analysis after quite a while being separate. But also there is a very practical context whereby many people from health economics and related backgrounds are working in the development of behavioural policies across a vast array of areas. The talk draws from papers with PhD students Karen Arulsamy and Lucie Martin as well as colleagues Leo Lades, Orla Doyle, Simon McCabe, and Conny Wollbrant.

i) One very simple idea is that policies will have differential treatment effects across levels of mental health. This could be due to differential decision making strategies but also due to the very widely studied phenomenon of poor mental health disrupting economic progression. Put simply, people with poor mental health live more complex administrative lives. In work I have conducted with Karen Arulsamy we show that mental health is a very strong predictor of pension coverage prior to autoenrolment in the UK. This is of course partly because of employment but also even within full-time employed individuals, pension coverage is far lower among people with poor mental health, controlling for a wide range of other factors. This gap disappears after autoenrolment.

ii) The second aspect I wanted to speak about more generally is the experience of administrative environments. In work with Lucie Martin and Orla Doyle, we look at how people experience administrative burden more generally. As can be seen, various markers of disadvantage select people into administrative environments that are more emotionally taxing. We also show that administrative burden is experienced as more discouraging for these groups. But focusing on experience itself is something worth reflecting on. Even if it did not alter the behaviour, there is an interesting ethical issue surrounding the type of psychological reaction we generate.

As a brief interlude, this is Brendan Bracken.

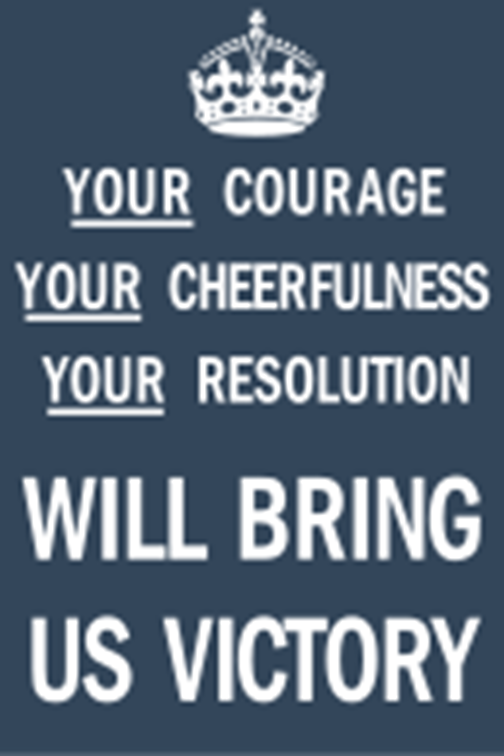

The inspiration for Big Brother. The Ministry for Information was a sort of wartime Nudge Unit that generated a lot of discussion. Has anyone seen these before? They generated quite a bit of controversy at the time (

excellent short paper on that here). Keep Calm and Carry on is often represented in modern media as exemplifying the stroic British spirit. It was deeply unpopular. Some of this may have reflected psychological reactions to the Ministry for Information itself amplified through media (something that indeed

might have happened recently in the UK with covid messaging). But I also think if you look at it carefully, it is not hard to see why people living in wartime conditions would have seen it as patronising to be given messages like this.

iii) With this in mind, along with Stirling colleagues Conny Wollbrant and Simon McCabe we have been looking more at how people experience different types of public messaging relating to health behaviour and the extent to which this would create both psychological reactions but also potentially unintended behavioural consequences. The example discussed in the talk focused on a proposal by the British government to include messages on medication bottles about the price and funding of the medication. As can be seen in the paper, likely engagement might be higher but so also would reported feelings of indebtedness and being a burden.

This is currently only illustrative and we are working on integrating such measures into live policy roll-outs. But in general, there is now a vast enterprise unfolding in deploying various types of psychological emotion modifications to influence people's behaviour. It will be important to examine potential for them affecting people in different ways. One thing we have examined is whether some type of ethical pre-mortem could be embedded to the appraisal process of large-scale behavioural work. FORGOOD. While we have not attempted something that would create a very generic scaled template for this, some scope for identifying particularly aversive psychological reactions is important and arguably an important capacity for behavioural teams working in these areas to have.

Thank you, hopefully there are some things of interest there. By way of conclusion, Mental health and human experience measures were largely taken out of economic analysis because they were too messy. Some would probably want to leave them out. But I think we will be moving rapidly in the direction of seeing appraisal and evaluation literatures that incorporate mental health and measured human experience in terms of ethical appraisal, heterogeneity analysis, and behavioural mechanisms.

Those of you who are working on these areas will face a lot of challenges so I will just finish by saying Keep Calm and Carry On.

References

Lades, L. K., & Delaney, L. (2022).

Nudge FORGOOD. Behavioural Public Policy, 6(1), 75-94.

No comments:

Post a Comment